Can Trauma be Passed Down Through Generations?

Words By Aspasia Celia Tsampas and Ania Wojas

Cover Art by Devon Smillie

The following article appeared in the November 2019 edition of The Campus.

Most people are aware of what traumadoes to one’s general health. Extreme stress caused by an event can alter notonly someone’s mental health, but physical health as well. However, is itpossible that the trauma of our ancestors and past generations can be passeddown to future generations?

In all the world’s tragediesthroughout history, many entire groups of people have undergone extreme stressand trauma. A recent study conducted by the Proceedings of the National Academyof Sciences (PNAS) suggests that the experiences of our parents, grandparents,and even great grandparents, may be passed down through our DNA-- allowingfuture generations to inherit that trauma. The study particularly looked atsurvivors of the Civil War, especially prisoners of war (POW) and theiroffspring. They found that the sons of army soldiers who endured gruelingconditions as POWs were more likely to die young than the sons of soldiers whowere not imprisoned. This pattern is despite the fact that the sons were bornafter the war, so they could not have experienced its horrors personally. Thestudy states that these findings are, “most consistent with an epigenetic explanation” and do notalign with other factors such as socioeconomic standing, family structure, etc.

Thisstudy is not the first time humans have questioned the likelihood of a geneticlink for trauma. A study analyzing Holocaust survivors at Bar Ilan Universityin Israel suggests that, “Holocaust survivors suffering from a post-traumaticstress disorder and their adult offspring exhibit more unhealthy behaviorpatterns and age less successfully in comparison to survivors with no signs ofPTSD or parents who did not experience the Holocaust and their offspring.”

Manymanifestations of inherited trauma have begun to be addressed in first generationimmigrants in the US, where seeking help for psychological distress and traumais more socially acceptable than in many other places around the world. Thisdistress is compounded by epigenetic accumulations of trauma throughout theyears. In their homeland, it is often the case that people suffer through warand death and do not have the option of acknowledging trauma, let alone seekinghelp for it, when it seems to be a natural part of life. When kids come to acountry where these issues are finally addressed, it may be difficult for theirparents to understand the extent of their suffering, or the idea that it can bealleviated. Education is key inunderstanding and overcoming inherited trauma.

FormerCUNY School of Medicine Assistant Professor in the Department of Molecular,Cellular & Biomedical Sciences, Dr. Michelle Juarez sheds some light on thegenetic component of trauma, stating that, “Not just mutations can contributeto our response to environmental factors. This is an especially importantconsideration for the mammalian reproductive cycle, because genetically weoriginally develop in our mothers before they are born. Therefore the exposuresof our great-grandmothers will affect our mothers and then be carried forwardto manifest during our lives. This epigenetic pattern of inheritance, e.g.heritable changes that alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence,can have dramatic results on future generations.”

Thereis current research being done on the topic by demonstrating how the model ofinheritance described by Dr. Juarez has the ability to alter immune systemfunctions. This injury can accumulate and be passed down through generations,impacting even immunity to the influenza virus. Multigenerational weakening ofthe immune system provides an explanatory model of why there is such extensivevariation of responses to both the flu and its vaccine, which cannot simply beexplained by accounting for age and virus mutations. In mice, testing of thishypothesis revealed that generations up to, and including, great-grandchildrencan be affected, with female mice being more affected.

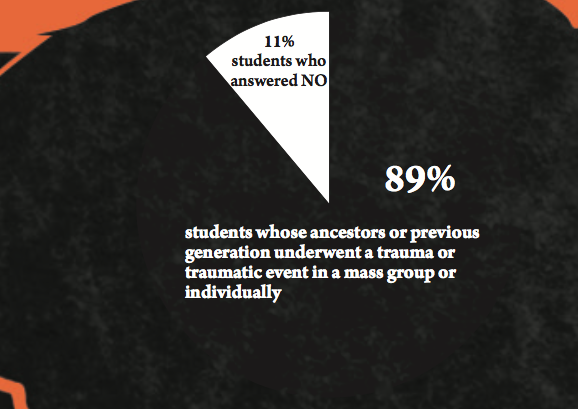

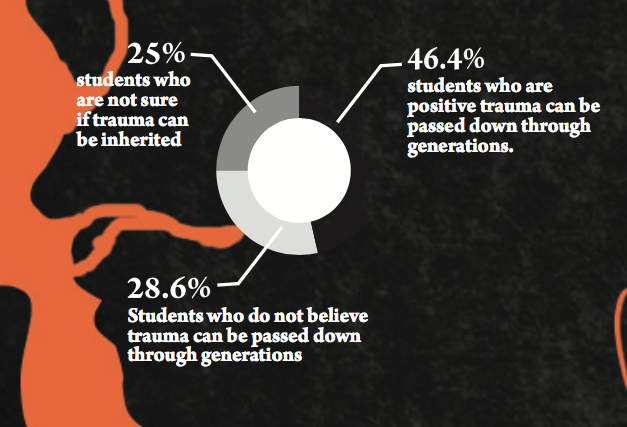

Togauge the opinions and experiences of students at The City College of New York,The Campus, conducted a survey onintergenerational and inherited trauma. The City College community is amongone of the most diverse in the world,housing students from all different backgrounds and experiences. Therefore,when asked if their ancestors or a previous generation underwent a trauma ortraumatic event, either in a mass group or individually, 89% of students whotook the survey answered yes. Nonetheless, of the same pool, when asked if theybelieved that trauma or traumatic events can leave a chemical mark on one'sDNA, causing it to be passed down through generations, the answers were mixed.Only 46.4% of students were positive in their belief that, yes, inheritedtrauma is passed down genetically, 28.6% were positive it was not possible atall, and 25% were simply not sure.

LaurenRosen, a third-year sociology major, believes inheriting trauma is verypossible, but is not sure whether this mark is genetic or psychological. Shestates, “I do think that inherited trauma would be capable of leaving apsychological mark, especially in the cases of those that trigger episodes ofdepression, PTSD, or generally involve other forms of mental illness. There isa genetic component to many of these conditions, regardless of the initialtrigger, and are somewhat likely to be passed down to future generations.”

Asa woman of Jewish descent, Rosen’s personal history of generational traumastems from her people’s experience in the Holocaust. While her family was luckyenough to have migrated to America, much of her family is still very much waryof the traumatic events that occurred in the 1940s, as well as the continuedlong history, both prior and after, of anti-Semitism. Rosen states, “Mygrandmother, who is particularly proud of our Jewish heritage, still remainsextremely wary of the anti-Semitism that fueled the Holocaust, as well assmaller-scale hate crimes all over the world. Her way of coping with thistrauma seems to be reassuring herself of our continued lineage, mainly byquestioning my sister and me about who will continue the traditions when she nolonger can herself. This creates stress and sometimes even a minute level ofguilt for both my sister and myself, as neither one of us really practices thisreligion.”ForRosen, inherited trauma functions more like a chain reaction, where the need tosurvive and continue their lineage and heritage, falls upon her. She states,“Younger generations do tend to reap the consequences of their elders’ traumas,and consequently, develop their own. I think that inherited trauma functionsmore like a chain reaction than a direct inheritance of particular traumas.”Further research must be done to better understand this link of human traumaticevents on our chemical composition, both genetically and psychologically, tohelp alleviate this notion.